| Original Article Online Published: 08 Jan 2024 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 199-213 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Paediatric haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institutionHaifa Ali Bin Dahman (1), Ali Omer Aljabry (2)(1) Associate Professor, Pediatric Department, Hadhramout University College of Medicine (HUCOM), Al-Mukalla, Yemen (2) Pediatric Neuro-Psychiatry, Care Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya Correspondence to: Haifa Ali Bin Dahman Associate Professor, Pediatric Department, Hadhramout University College of Medicine (HUCOM), Al-Mukalla, Yemen. Email: Bin_Dahman.H [at] hotmail.com Received: 30 July 2020 | Accepted: 18 February 2023 How to cite this article: Dahman HAB, Aljabry AO. Paediatric haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(2):199–213. https://doi.org/10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

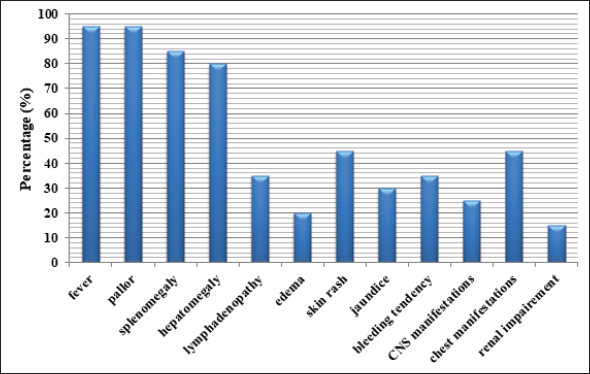

ABSTRACTPaediatric haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (pHLH) is a potentially life-threatening condition with significant diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical presentation, the diagnostic challenges, and the outcomes of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in children assessed at Mukalla Hospital, Yemen. Data from 20 medical records of HLH patients admitted between January 2010 and May 2022 were retrospectively analysed. The median age at presentation was 3.5 ± 5.1 years. Male: female ratio was 1:1. The median time for referral to the hospital was 30 ± 64 days. The most common clinical manifestations were fever and pallor in 95% of cases, and splenomegaly (85%). Hepatomegaly, chest, renal and neurological manifestations were detected in 80%, 45%, 15% and 20% of cases, respectively. Bone marrow haemophagocytosis was detected in 60% of cases. Sixteen patients fulfilled the HLH diagnostic criteria, and 11 patients (55%) received the HLH 2004 protocol. Out of the 20 patients, three (15%) patients are alive. Fourteen patients died, with overall mortality of 82.35%. All mortalities were due to HLH disease with multi-organ failure. Relapse was noticed in five patients either during treatment or after full recovery. pHLH is a challenging emergency with a high mortality rate. High clinical suspicion is essential for early detection and intervention to improve the prognosis. KEYWORDS:Cytokine; Familial; Ferritin; Haemophagocytosis; Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; Pancytopenia. INTRODUCTIONHemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening condition associated with infections (viral, bacterial, and parasitic), malignancies, rheumatologic conditions and immune deficiencies [1,2]. It is classified into primary (familial) and secondary (reactive) disease. Sharing the same spectrum of non-specific symptoms between these two subtypes raises the challenge of accurate diagnosis and rapid treatment initiation [3]. About 1 in 100,000 children under the age of 18 are thought to have HLH. However, this estimation is likely to be low [2], and now it is increasingly recognised [4]. Despite recent advances in research, a lot of curiosity surrounds the pathogenesis of HLH [5]. The aetiology of HLH is attributed chiefly to defective (low or absent) cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells’ Ag-mediated cytotoxicity [6]. This dysfunction results in a cytokine storm, causing damage to the vascular endothelium and myelosuppression [7,8]. The systemic infiltration of activated lymphocytes and macrophages causes hematologic cytopenias, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, lymph node enlargement, splenomegaly, skin rash, oscillating fevers and central nervous system (CNS) manifestations ranging from seizures and/or localised deficits to encephalopathy [9]. High mortality risk accompanies the acute stage of the disease [7]. Delay in diagnosis and initiation of immunosuppression results in a rapid progression to multi-system organ failure (MOF) [10]. Allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation is indicated in familial, relapsing, or severe/persistent cases [11]. In this study, we retrospectively describe the clinical features, diagnostic issues, and treatment outcomes of children with HLH at a single institution in Yemen over 12 years. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case series of paediatric HLH (pHLH) from Yemen reported in the literature. MATERIAL AND METHODSA retrospective study was conducted at Mukalla Maternity and Childhood (MCH) Hospital, in Mukalla City, Hadhramout Province, Yemen, from January 2010 through May 2022. The criteria for diagnosis were based on the proposed 2004 HLH diagnostic criteria of the Histiocyte Society (Table 1) [11,12]. Case records of children diagnosed with HLH were reviewed. The following details were collected and analysed: age at presentation, sex, relevant family history, presenting clinical features (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, bleeding tendency, jaundice, oedema, chest manifestations, CNS manifestations and renal impairment), laboratory investigations, aetiology, the referral time, which is the lag period between disease onset and first presentation to the hospital, treatment used, and outcomes. Primary HLH was highly suspected in patients with a younger age group, positive parent consanguinity, and a family history of the same presentation. However, genetic studies were needed for confirmation as the viral infection might trigger both primary and secondary HLH (sHLH). Fibrinogen, sCD25, and NK cell function were done in a few patients who could travel abroad for further evaluation. Genetic studies were not available in our country. Some patients in our study did not meet defined diagnostic criteria. However, they were still diagnosed and treated as HLH at our institution. They were included in the current study as the clinical course supported the diagnosis. On the day of diagnosis, therapeutic options included the use of supportive treatment, corticosteroids (dexamethasone, methylprednisolone) alone or with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), etoposide, cyclosporine (CSA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and methotrexate (MTX). Relapse was defined as disease reactivation after clinical and laboratory remission; the patient develops ≥3 of 8 diagnostic criteria or new CNS symptoms. MOF was defined as a disease requiring resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, or inotropic support. Statistical methodsAll collected data were entered and analysed using SPSS 24. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, medians, SDs and graphs, were applied. RESULTSDuring the study period of 12 years, 20 patients (2010–2015=6, 2016–2022=14) were diagnosed and treated for HLH. The age ranged from 0.14 to 14 years, with a 1:1 male: female ratio. The median age at diagnosis was 3.5 ± 5.2 years. Fever of unknown origin was the most common presentation on admission (65%). The median time for referral was 30 ± 64 days (2010–2015=90 ± 58.9 days, 2016–2022=21 ± 59 days). Table 1. HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria.

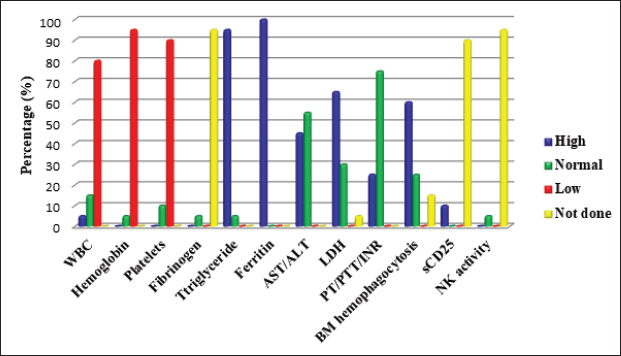

HLH was attributed to different aetiologies including infection (leishmania=2, Dengue=1, non-specific infection=4), haematology/oncology (leukaemia=1, sickle cell anaemia=1), rheumatology (systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)=1, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA)=1), and primary immunodeficiency (Griscelli syndrome (GS2)=2, Chediak-Higashi (CHS)=2, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)=1). The underlying cause was not identified in four cases. Parental consanguinity was detected in 11 (55%) cases and a family history of sibling death with a similar presentation was noticed in seven (35%) cases (Tables 2 and 3). The most common clinical and laboratory manifestations are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Treatment and outcomesIVIG and steroids (dexamethasone or IV methylprednisolone) were used in 11 (55%) and 13 (65%) cases, respectively. Chemotherapy was initiated in nine children with HLH who did not respond to IVIG and steroids; etoposide in four (44.4%) patients, CSA in eight (88.9%) patients, and MMF in one (11.1%) patient. Intrathecal MTX was used in one patient with encephalopathy. One patient was critically ill; he was not fit for chemotherapy. Four patients did not start a specific HLH protocol as they were lost to follow-up. The use of biologics and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was not a practical option for our patients. Out of 20 children with HLH, two (10%) recovered completely, and one is still on treatment. 14 patients died, giving overall mortality of 82.35%. During hospitalisation, extensive flesh-eating infection, intestinal obstruction, transfusion-associated graft versus host disease, and gastrointestinal bleeding (upper and lower) were noticed. Five patients died after relapse. One patient relapsed during treatment and four patients relapsed 2–10 months after full recovery; one patient had progressive encephalopathy (hemiplegia, left-sided facial palsy, and loss of consciousness), and another patient was not compliant with maintenance treatment of SLE. She presented with a history of recurrent blood transfusion and died with intractable heart failure. The last two presented with progressive HLH that was complicated with convulsions and coma. All deaths were attributed to disease reactivation with MOF (Tables 2 and 3). Table 2. Clinical and laboratory parameters of HLH cases at Mukalla MCH Hospital, Yemen.

ALL, Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; CSA, cyclosporine; Dexa: dexamethasone; FUO, fever of unknown origin; FU, Follow up; ITMTX; Intra thecal methotrexate; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; IVMP, intravenous methyl prednisolone; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; N, normal; SCA, Sickle cell anaemia; SLE, Systemic lupus erythematosus; SOB, shortness of breath. Table 3. Clinical and laboratory parameters of HLH at Mukalla MCH Hospital, Yemen.

CHS, Chediak-Higashi syndrome; CSA, cyclosporine; Dexa, dexamethasone; FUO. fever of unknown origin; GIB, Gastrointestinal bleeding; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; IVMP, Intravenous methyl prednisolone; Loss FU, lost to follow up; N, normal; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; SJIA, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; TAGVHD, transfusion associated Graft-versus-host disease.

Figure 1. Clinical manifestations of pHLH patients. CNS, Central nervous system.

Figure 2. Laboratory manifestations of pHLH patients. ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase, BM, Bone marrow; INR, International normalised ratio; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase, NK, Natural killer cells; PT, Prothrombin time; PTT, Partial thromboplastin time; WBC, White blood cell count. DISCUSSIONHLH is a severe, sometimes fatal hyper-inflammatory condition brought on by an overstimulated, inefficient immune response. As a result, uncontrolled production of activated lymphocytes and macrophages could result in MOF [13]. One in 100,000 children under the age of 18 is thought to have HLH, regardless of race or ethnicity [2]. According to estimates from Sweden, familial HLH (FHLH) affects 0.12 out of every 100,000 children [12,14]. These findings were most likely understated either because there were unpublished cases [2] or because the diagnosis was challenging [4,15]. Recent advancements in diagnosis and case detection have led to an increase in the observed overall incidence [4]. It is frequently seen in infants, although it can occur at any age [4,16,17]. From in utero with hydrops fetalis up to the age of 70, Weitzman [5] described a main primary HLH presentation. A male-to-female ratio of around 1:1 was reported [18]. In line with the earlier reports, our results showed that the age of our patients ranged between 0.14 and 14 years (median 3.5 ± 5.2 years) with a 1:1 male-to-female ratio. Primary HLH is an autosomal recessive [11,19], or X-linked [20] disease. Nine genetic mutations controlling CTLs/NK cells cytotoxicity have been connected to primary HLH advancement to further subdivisions into (FHLH 1–FHLH 5) and HLH associated with GS2, CHS, Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome type 2, and X-linked lymphoproliferative disease types 1 and 2 [1,13]. Immunodeficiency syndromes including X-linked SCID and X-linked hypogammaglobulinaemia, as well as inborn metabolic abnormalities, can also manifest with HLH [1,5,13,21]. sHLH is usually acquired (no inheritance). It is triggered by bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic (mainly leishmaniasis) infections [22], malignancy (particularly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma), drugs [23,24], and autoimmune diseases such as sJIA and SLE [6,25]. In the latter cases, it is often called macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) [5,9,11]. Sawhney et al. [26] reported a 6.8%–7% association between MAS and sJIA. In China, no aetiological cause was identified in 56.2% of pHLH [16]. Epstein-Barr virus was reported as a significant trigger for primary and sHLH in Asian countries [1,5,16,19,22,27]. Nandhakumar et al. [4] and Ellis et al. [28] reported dengue contribution of the total infection-induced sHLH in 52% and 67%, respectively. Other viral infections, such as hepatitis A, parvovirus 19, varicella, coxsackie, cytomegalovirus [23,24], avian flu (H5N1) [29], adenoviruses, and herpes viruses, may also trigger sHLH [27]. In our study, variable aetiologies were detected, including primary immunodeficiency in five (25%) cases; infection in seven (35%) cases; rheumatological causes in two (10%) cases; and hematology/oncology in two (10%) cases. The underlying cause was not identified in four cases. Positive consanguinity and family history of similar cases were detected in 11 (55%), and 7 (35%) cases, respectively. Previous studies reported sporadic cases of FHLH with no apparent family inheritance [7,16,25]. In our institution, it was difficult for us to differentiate between primary and sHLH as no genetic study was available. Diagnostic recommendations for HLH considering clinical highlights, research facilities, and histopathological examinations were conceived by the Histiocyte Society in 1991 and were refreshed in 2004 [11,12,30]. HLH patients could present other biochemical parameters, including elevated transaminases, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-Dimers, and elevated cerebrospinal fluid cells or protein [5]. In 2009, hepatitis was included as a diagnostic criterion (modified 2009 HLH criteria) [19]. As specific HLH criteria may not be applied to patients with sJIA, modified diagnostic criteria specific to MAS were suggested by Ravelli et al. [31]. The sensitivity of HLH diagnostic criteria for early HLH is unknown [9]. None of these eight criteria are specific for HLH diagnosis, and they might be found in disseminated infections and several systemic and inflammatory conditions [8–10]. HLH diagnoses are known to follow an atypical course; some may have severe systemic symptoms [1,32] and others may not have fulfilled the diagnostic criteria on presentation [3,12], including newborns [33]. All these factors might explain the difficulty and delay in recognition and referral as reflected by the long lag time between disease onset and diagnosis [4,7]. Hence, the progression of the criteria should alert physicians of the possible presence of HLH [33] as the disease manifestations may evolve [4,21]. In our current study, 16 patients fulfilled HLH diagnostic criteria at presentation, and we noticed an improvement in the referral time during the last 7 years (2016–2022) with a median time of 21 ± 59 days in comparison to 90 ± 58.9 days in the period from 2010 to 2015. This was attributed to the early referral of any patient with unexplained prolonged fever, pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly. It is evident from the variety of presentations that primary care physicians, intensivists, and different subspecialists, all need to recognise the early signs of HLH and pursue appropriate diagnostic evaluations [10]. Fever and splenomegaly are early markers of pHLH (except in newborns) [8,34], although both are not specific to HLH [35]. In our study, prolonged fever and splenomegaly were documented in 95% and 85% of HLH cases at the time of presentation, respectively. Previous reports documented fever in 91% [18] and 100% of cases [4,7,20,23] and splenomegaly in 85.7% [7] and 84% [18] of pHLH cases at the initial presentation. CNS involvement is a significant independent prognostic factor for pHLH [36]. It represents a late stage of disease and is the primary cause of morbidity in long-term survivors [36]. Neurologic symptoms, either isolated or associated with systemic findings [37], were seen in up to 37%–75% of pHLH cases [14,16,18,24,25,36,38]. These symptoms include lethargy, irritability, disorientation, headache, hypotonia, nerve palsies (VI–VII), seizures, dysarthria, dysphagia, coma, blindness, ataxia, hemiplegia/tetraplegia, signs of increased intracranial pressure, and encephalitis like presentation [8,9,20,30,36]. Unfortunately, even in the absence of neurological abnormalities, mononuclear cell pleocytosis (lymphocytic meningitis)/albuminocytologic dissociation [8] or abnormal brain computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings can be observed at the onset or during the progress of the disease [11]. In our study, seizures were noticed in four patients (20%); one patient with Griscelli syndrome presented with recurrent encephalitis and papilledema. Later on, she developed hemiplegia, left-sided facial palsy, and loss of consciousness. In our study, other general and systemic involvement was similar to previous studies [1,18,21,23,25,30,38,39]. Bi/pancytopenia may not be present in the early stage of the disease [31,40], and severe pancytopenia requiring repeated transfusions may emerge as the disease progresses into HLH [41]. During cytopenic events, patients’ BM aspirates have been observed to be hypo-cellular, normo-cellular, or even hyper-cellular [40]. Patients’ leukocyte counts at diagnosis vary, but most have anaemia and/or thrombocytopenia [38,41]. Nandhakumar et al. [4] reported anaemia and thrombocytopenia in 51% and 73% of cases, respectively. Chan et al. [7] reported pancytopenia in 100% of patients. In comparison, our current study showed variable leucocyte counts among HLH patients. Anaemia and thrombocytopenia were present in 95% and 90% of cases, respectively. Although not specific [16], ferritin is considered an important marker for diagnosing and evaluating HLH disease activity [42]. Ferritin level above 500 µg/l is 84% sensitive [12] and high levels >10,000 µg/l in children have 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity for HLH [42]. However, some HLH patients might have ferritin levels slightly above normal [5]. A rapid reduction in ferritin levels after treatment initiation is correlated with better survival in patients with pHLH [43]. Hyperferritinaemia was detected in 100% of our patients compared to 96% [4] and 66.7% [23] of pHLH cases reported previously. Identifying haemophagocytosis in tissue biopsies is not essential to diagnose pHLH if the clinical presentation and additional diagnostic test results strongly implicate HLH [5,35,44]. Previous studies reported variable results ranging between normal BM cytology [4,25,38,45] and haemophagocytosis in 30%–40% up to 96.8% of pHLH patients either at initial presentation or during disease progression [4,30,32,33,44]. In the current study, BM haemophagocytosis was detected in 60% of cases, while 25% of cases had normal BM cytology. High levels of triglycerides (95%), transaminases (45%) and LDH (65%) in our patients were consistent with previous studies [1,3,17,18,25,32,33]. The HLH Study Group of the Histiocyte Society designed an HLH (1994/2004) treatment protocol (based on etoposide [VP-16], dexamethasone and cyclosporine) suitable for the initial treatment of all forms of HLH (except MAS) [5,11,12,40]. Nandhakumar et al. [4] adopted a simplified algorithm to guide the evaluation and management of pHLH in resource-limited settings. HLH treatment aims to suppress cytokine storms and to control CTLs/NK defective cytotoxicity, causing life-threatening consequences [13,22]. Not all patients with pHLH need to be started on the full HLH 2004 protocol. The majority of children with sHLH improve with supportive care alone [4]. Patients with MAS may respond to corticosteroids alone or a combination of corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and/or IVIG [5] even for cases severe enough to warrant intensive care unit attention care [24,46]. Patients with CNS HLH should generally receive intrathecal steroids and MTX [37]. In the case of infection-related HLH, treatment of the causative agent alone is insufficient, and a conventional HLH regimen should be used [13]. Only leishmania-associated HLH necessitates exclusive amphotericin B treatment [47]. In our study, treatment included steroids and IVIG+/-chemotherapy. Eleven (55%) patients received the HLH 2004 protocol. Intrathecal MTX was used in one patient with progressive CNS manifestations. One patient with leishmania was treated successfully with amphotericin B (not in our institution). In some cases, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) combined with steroids may be a viable option for etoposide [48]. Ruxolitinib, emapalumab, anakinra, and alemtuzumab have been suggested as salvage therapies for patients with refractory disease [13]. HSCT was indicated in patients with FHLH, relapsing, severe persisting disease [7], and CNS progression [36] with survival improvement ranging from 50% to 92% [1,11,38]. Unfortunately, the options of ATG, biologics, and HSCT were not available and expensive for our patients. The survival rate of children with HLH was poor [2,5]. Advances in therapeutic protocols improved the 5-year survival for pHLH from 5%–22% to 55%–63% [1,12,14,48]. However, pHLH is still associated with high morbidity and mortality [32] of approximately 33%–63% [2,14,20,44], up to 70%–85% in certain subtypes [27]. In our study, the mortality rate during 2010–2015 was 100% (5/5) in comparison with 75% (9/12) during the period from 2016 to 2022. The overall mortality over the study period was 82.35%, mostly related to disease reactivation with MOF. Several risk factors associated with increased disease resistance, mortality, adverse outcomes, and poor prognosis in pHLH patients have been previously reported [32,35,39,49]. Diagnosis of pHLH is considered a challenge for clinicians (especially in developing countries). This might be due to:

It is worth mentioning that despite our restricted sample size, limited access to advanced diagnostic tests, and the retrospective nature of the study, it was possible to concentrate on the significance of HLH as a challenging emergency in a paediatric population. CONCLUSIONpHLH diagnosis is a big dilemma for physicians because of its vague and variable presentations; patients may be critically ill or not fulfilling the diagnostic criteria at early presentation. Thus, early diagnosis requires a high clinical suspicion, a thorough awareness of the clinical manifestations of pHLH, and careful evaluation and follow-up of a child who doesn’t yet present the whole picture of HLH. Early detection and effective treatment will optimise the prognosis. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONSATG Anti thymocyte globulin BM Bone marrow CHS Chediak–Higashi syndrome CNS Central nervous system CSA Cyclosporine CTL Cytotoxic T lymphocytes FHLH Familial haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis GS2 Griscelli syndrome type 2 HLH Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis HSCT Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin LDH Lactate dehydrogenase MAS Macrophage activation syndrome MMF Mycophenolate mofetil MOF Multisystem organ failure MTX Methotrexate NK Natural killer pHLH Paediatric haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis SCID Severe combined immunodeficiency sHLH Secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis sJIA Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. FUNDINGNone. ETHICS APPROVALThe study is a record retrospective study. No names were used for data collection. Participants consent is not required according to the approved research guidelines of Hadhramout University (Ethical Committee of Hadhramout University College of Medicine). Confidentiality was maintained by omitting any personal identifying information from data collection. REFERENCES

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Dahman HAB, Aljabry AO. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 Web Style Dahman HAB, Aljabry AO. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=92398 [Access: January 22, 2025]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Dahman HAB, Aljabry AO. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Dahman HAB, Aljabry AO. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited January 22, 2025]; 23(2): 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 Harvard Style Dahman, H. A. B. & Aljabry, . A. O. (2023) Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudan J Paed, 23 (2), 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 Turabian Style Dahman, Haifa Ali Bin, and Ali Omer Aljabry. 2023. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (2), 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 Chicago Style Dahman, Haifa Ali Bin, and Ali Omer Aljabry. "Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Dahman, Haifa Ali Bin, and Ali Omer Aljabry. "Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.2 (2023), 199-213. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Dahman, H. A. B. & Aljabry, . A. O. (2023) Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical presentation and outcome of 20 patients at a single institution. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (2), 199-213. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1659160002 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Hafsa Raheel, Shabana Tharkar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 28-38

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.5

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12

Cited : 8 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mustafa Abdalla M Salih; Satti Abdelrahim Satti

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(2): 4-5

» Abstract

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Hasan Awadalla Hashim, Eltigani Mohamed Ahmed Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 35-41

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.4

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mutasim I. Khalil, Mustafa A. Salih, Ali A. Mustafa

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 10-12

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.1061585398078

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]