| Original Article Online Publishing Date: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 187-198 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Opportunities, barriers and expectations toward international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi ArabiaNouf Al Kaabi (1,2,3), Mohammed Aldubayee (1,2,3), Emad Masuadi (1,3), Ibrahim Al Alwan (1,2,3), Amir Babiker (1,2,3)(1) King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (2) King Abdullah Specialized Children’s Hospital, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (3) King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Correspondence to: Nouf Al Kaabi King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Email: nouf.m.alkaabi [at] gmail.com; alkaabino [at] ngha.med.sa Received: 06 October 2020 | Accepted: 12 November 2023 How to cite this article: Al Kaabi N, Aldubayee M, Masuadi E, Al Alwan I, Babiker A. Opportunities, barriers and expectations toward international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(2):187–198. https://doi.org/10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

ABSTRACTThe objective is to assess the feasibility, barriers, expectations and motivation of health trainees in Saudi Arabia regarding medical missions. This study seeks to fill the gap in global health curricula and regulations, as well as provide guidance for trainees participating in international health electives in Saudi Arabia. This cross-sectional survey of health trainees (in medical, surgical and other allied health professions) was conducted across Saudi Arabia from March 2017 to February 2018 using a standardised survey adapted to assess expectations, barriers, awareness of available opportunities and the effect of mentorship in improving motivation toward medical missions. A total of 589 respondents completed the survey, with a response rate of 83.7%. Most respondents were under 35 years old, with an equal sex distribution. Furthermore, the respondents primarily had medical and surgical specialties training and graduated from the western region of Saudi Arabia. Health trainees who considered volunteering during training but did not have previous experience in missions acknowledged that the presence of a staff member experienced in missions in their training environment positively affected their interest in missions (p=0.038). The most common reasons for interest in volunteerism were to enhance one’s own technical and clinical skills and help others in need. Interest in tourism and learning about new cultures are additional reasons. Only 7/589 participants had experience and expressed the barriers they faced during volunteerism. Interestingly, their colleagues who did not have a similar experience perceived almost the same barriers. A major barrier faced by experienced participants was the ‘lack of elective time’, compared to the ‘lack of available organised opportunities’ by the inexperienced group. In conclusion, coordinating health trainees’ missions through a unified authoritative body would provide better opportunities, override challenges and improve their perceptions and participation in these missions. KEYWORDS:International health; Medical missions; Residency; Saudi Arabia; Training; Volunteering. INTRODUCTIONHealthcare workers and doctors are distributed unevenly worldwide. Recent data show that countries with the lowest health needs have the highest number of healthcare workers and vice versa. For example, African countries suffer from more than 22% of the global burden of diseases but have access to only 3% of healthcare workers [1]. This gap in the need for healthcare personnel is projected to persist until 2030, particularly in the Middle East and Africa [2]. To reduce these deficiencies, healthcare communities have begun arranging short-term medical and surgical missions that actively participate in patient care and address shortages in healthcare staff in these areas. The terms medical and surgical missions have been adopted to differentiate them from relief missions that occur during disasters. They include voluntary trips by established relief organisations and trips that health trainees undertake under the umbrella of training programs [3]. Initially, these missions were largely unregulated and often lacked evaluation procedures. They are also largely disorganised and diverse; therefore, healthcare providers are left with their impetus [4]. Nowadays, these missions are morphing into more formal and well-planned international health electives and global health education that take part in training programs for undergraduate and postgraduate candidates. These short-term experiences should be undertaken based on the needs and goals of the hosting community and done in a way that ensures that both parties have a bidirectional exchange of benefits. Upholding ethical principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, nonmaleficence and justice is paramount [5]. In the context of the Middle East and North Africa, one of the most amazing experiences was initiated by the University of Gezira, Sudan, since its establishment in 1978. They came up with the idea of the Integrated Field Training, Research and Rural Development Program where they exposed their medical students to rural settings in the community of Sudan itself with very positive feedback [6]. With an appropriate predeparture training curriculum that includes ethical, cultural and clinical objectives, these missions can have enormously positive effects on both health trainees and host institutions. The positive effects of hosting institutes include improving patient care and bringing new aspects into staff education [7]. These trips can also enhance health equity and help advance international health initiatives [8]. Health trainees had a greater appreciation for the public health system and more knowledge of the challenges faced by communities with limited resources [9]. As reported by health trainees who had previously undergone this experience, missions also improved their clinical skills and led to improved resourcefulness and cost-effectiveness [10]. These trips add to the residents’ cultural competency, a part that is often not faced in their own home country [11]. Prior studies showed that lack of time was the most detrimental factor holding the trainees back and that it would be greatly helpful if support was provided through covering duties or giving time off for those intending to participate [12]. Concerns have been raised regarding the health and safety of health trainees during medical and surgical missions. Rowthorn et al. [13] questioned whether such short-term experiences could have the potential for illegal practices, giving undertrained participants more privileges they did not deserve. Nonetheless, these concerns can be successfully addressed and handled by following universal global health practice guidelines such as the American Academy of Paediatrics consensus guidelines and the Working Group on Ethics for Global Health Training guideline [14,15]. This study aimed to assess the feasibility and barriers to voluntary international health missions and the motivation and expectations of health trainees in Saudi Arabia toward these international health electives in resource-limited settings. In addition, the study explored candidates’ perceptions during preparation for a mission or within the duration of the mission itself. MATERIALS AND METHODSStudy design and settingsThis cross-sectional survey of health trainees across the medical, surgical and allied health fields was conducted all over Saudi Arabia from March 2017 to February 2018, with those enrolled in training programs across the eastern, central, western, southern and northern regions. An anonymous quantitative standardised survey in English was adapted with written permission from Matar et al. [16], and distributed online using the SurveyMonkey software. Subsequently, it was confidentially emailed to participants through the trainees’ contact list and social media of the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHSs). The survey measured health trainees’ motivations, attitudes and perceptions toward international volunteerism. The estimated time to complete the survey was 12 minutes, and because no personal or sensitive data were collected, consent was considered implicit if the survey was completed and submitted. To assess the feasibility, barriers, motivations and expectations of health trainees in Saudi Arabia toward international missions, we used the survey presented in (Appendix A). In addition, we surveyed our participants to assess their awareness of the available mission opportunities and the influence of mentorship on their decisions to volunteer abroad during and before residency by asking the following questions:

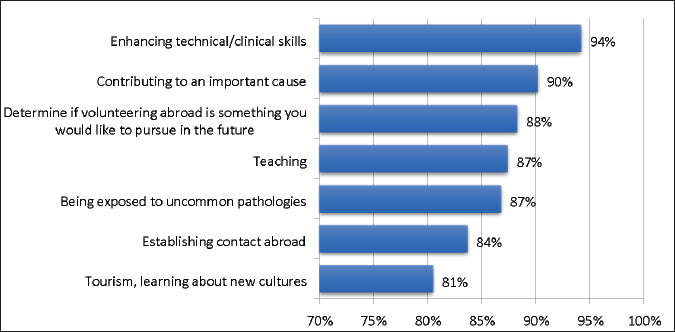

Study subjectsAll Saudi health trainees enrolled in medical and surgical specialties across the central, eastern, western and southern regions of Saudi Arabia were included. Based on this, we excluded answers from a participant who was no longer a trainee at the time of the survey and trainees from outside Saudi Arabia. Utilising SCFHS definitions, a trainee is a physician or specialist currently registered to be trained on one of the SCFHS-approved medical and surgical boards in a health institute (training centre) and accredited to host the training program [17]. According to the SCFHSs annual reports, at the time of the study, there were 8,552 health trainees enrolled in different medical and surgical training programs across Saudi Arabia: 3,421 residents in the central province, 3,020 in the western province, 1,411 in the eastern province and 700 in the southern province. Health trainees were distributed among 230 training centres and 79 training programs. Sample size and statistical analysisWith a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 5%, the required sample size was estimated to be 345, referring to a previous study [16] that was conducted in Canada among residents from two surgical subspecialties in which the positive perception toward international voluntary work among residents was 63.8%. Data were entered and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Bar charts were used to graphically present the categorical data. For inferential statistics, we used the chi-square test to assess the association between categorical data. A test was considered significant if the p-value was <0.05. Moreover, we analysed data for candidates with previous experience volunteering as students but not at the training level. We analysed this category separately because such an experience, even at the pretraining level, could have influenced the perception of these participants at the time of our study. RESULTSIn total, 709 participants responded to the survey. Of these, 61 were excluded because they had already secured their consultant positions by the time of data collection, 7 were excluded because they were trained outside Saudi Arabia and 52 did not complete the survey. The response rate was 83.7% (589/709). The demographics of the respondents are reported in Table 1 (93.7% under 35 years of age), with almost equal sex distribution. The majority were from medical (55.2%, n=325/589) and surgical specialties (30.4%, n=179/589) and graduated from universities in the western, central and eastern regions (46.2%, 31.2% and 16.3%, respectively). In the survey, 91% answered yes to having considered volunteering abroad as a resident (Table 2). The reasons for interest in volunteerism among health trainees with no previous experience in missions were enhancing technical and clinical skills and contributing to an important cause – helping others. Participants rated these as the most important (Figure 1). Other reasons included determining whether volunteering abroad was worth pursuing in the future, willingness to teach, exposure to uncommon pathologies, establishing contacts abroad for future collaboration, tourism and learning about new cultures (Figure 1). Table 2 shows the relationship between the trainees who considered volunteering and the presence of staff or mentors with experience in their surroundings. Table 3 presents studies on the same relationship but from the point of view of those who volunteered before joining their training program. Health trainees who considered volunteering as residents but did not have prior experience reported that the presence of a member experienced in missions positively influenced their interest in international health electives (p=0.038) (Table 2). The influence of a staff member within the department who actively engaged in medical missions significantly affected individuals with prior volunteering experience before enrolling in a training program. In contrast, for those without prior volunteering experience, this staff member had a direct impact on their inclination to contemplate the idea (p=0.002) (Table 3). Table 1. Demographics of the participants, N=589.

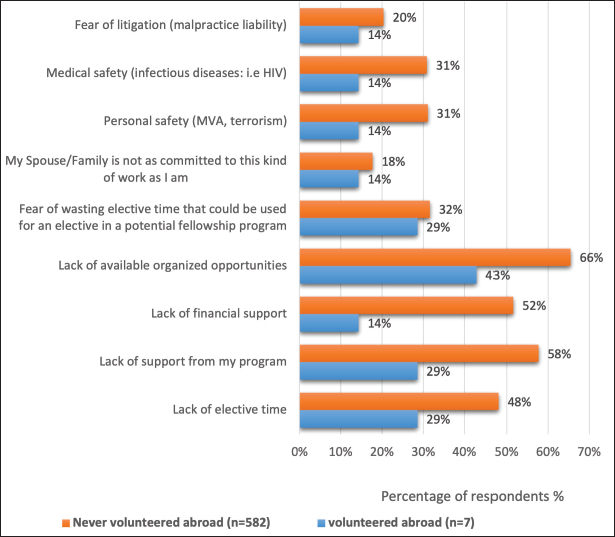

**Others include radiology, clinical pharmacy, pathology and physical and rehabilitation medicine. Only seven participants had experience in missions, and we expressed the barriers they faced during volunteer missions. The main barrier faced when they first made the decision is the lack of available organised opportunities followed equally by the lack of time and support from the training program. Interestingly, 582 colleagues with no previous experience in volunteer missions had similar perceived barriers. We combined the barriers that were considered problematic in both groups (Figure 2). The primary barrier faced by both groups was a ‘lack of available organised opportunities’. ‘Lack of financial support’ was a major concern in the group with no previous experience but not in those with experience. In addition, the group that had not previously participated in missions was concerned about the ‘lack of support from their training programs’. In addition, other potential barriers explored with variable degrees of importance for each included malpractice liability, personal safety (e.g., motor vehicle accidents and terrorism), not being supported by a spouse or family, fear of wasting elective time and fear of infectious diseases. Table 2. Impact of experienced mentors/staff on trainees considering volunteering during their training period (N=582).

Significant p values < 0.05 have been written in bold.

Figure 1. Reasons of interest in volunteering among trainees with no prior experience (N=582). DISCUSSIONIn Saudi Arabia, more organised opportunities, global health programmes and outreach missions as part of an official training curriculum are required. Currently, no clear or published guidelines exist for health trainees in Saudi training programs who wish to participate in such missions. Most published literature focuses on volunteerism in rural areas of Saudi Arabia or participation in health campaigns. Internationally, these missions have been extensively researched and developed since the 1980s [18,19]. Ninety-one percent of the trainees indicated that they considered volunteering abroad which shows increasing enthusiasm and need for participation in international volunteer clinical missions. Unsurprisingly, their international colleagues shared similar enthusiasm over the years and across the contents [20]. Table 3. Impact of experienced mentors/staff on trainees involved in volunteering before the training period (N=582).

Significant p values < 0.05 have been written in bold. The main interest expressed by the trainees was to enhance their clinical skills in future practice, gain confidence and self-satisfaction, and serve those in need. Health trainees from the central and western regions and those in surgical, critical and acute care specialties represented the majority of the responders. Since the survey was distributed equally to all trainees around Saudi Arabia, this finding could be because they had exposure to more opportunities or have met with people who participated in these specialties. All reasons for interest explored through the survey used in previous similar studies were rated as significantly important by the participants. This reflects a shared platform of perceptions and perspectives among health trainees from other parts of the world, as described in previous studies [16,21]. In our cohort, the lack of previous role models in training centres was a significant barrier to joining these missions. In contrast, there are many well-established examples in the literature of training programs that are full of role models [22,23]. One of the many was The School of Public Health at the State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center, which has provided up to 2 months of global health rotation for its students since the 1980s. The faculty members supported the experience as designated mentors, and the participants were fully prepared [19]. The presence of a role model who regularly participated in medical missions had a positive influence on interest in international health electives in our cohort among those who were considering participating in missions and had no prior experience (Table 2). Understandably, this did not significantly affect health trainees with previous mission experience before joining their training programs (Table 3). At the time of the study, the health trainees listed ‘lack of available organised opportunities’, ‘lack of elective time,’ ‘support from health trainees’ program’, and ‘lack of financial support’ as the main potential barriers to having a successful experience. The two most detrimental barriers for health trainees were a ‘lack of elective time and organised opportunities’. For those with experience, a ‘lack of organised opportunities’ was the main barrier, followed by a ‘lack of elective time’. Those who wish to participate in such an experience mentioned ‘lack of organised opportunities’ as the number one barrier, followed by ‘lack of elective time’.

Figure 2. Actual barriers faced by trainees who volunteered during their training n=7 and never volunteered n=582. *MVA: Motor vehicle accidents; **HIV-Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Organised opportunities fully supported by training programs are almost nonexistent, and the available opportunities are not well advertised [24]. Internationally, the scarcity of opportunities is a major concern. In response to this, numerous training programs have been trying and experimenting with new ideas to intergrade these missions with their well-established programs [25]. New programs and opportunities, some very creative, keep showing up, such as combining the paediatric emergency fellowship with the global health fellowship [26]. At the time of the study, physicians in consultant posts were encouraged to join volunteerism organised by non-governmental organisations working at the national and international levels. They travel on missions for international relief and target surgical and medical trips. For health trainees, opportunities for national programs or activities are achievable, but international opportunities are limited. However, more recently, international volunteering programs have been exclusively organised as per national policy by one authoritative body, King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center (Ksrelief), which will help mitigate some of the perceived barriers as per the candidates’ ambitions [27,28]. Ksrelief [27] was established in 2015 to provide humanitarian aid and relief in all sectors, including supporting health needs outside the borders of Saudi Arabia. It covers more than 69 countries across four continents [27]. Being a health trainee in an organised training program connotes obligations, tightly packed rotations, and electives with a short time for vacations [29]. If a health trainee decides to use their elective time in these missions, it will require an infinite process and coordination at multiple administration levels because there is still no clear official pathway to accommodate such voluntary training opportunities [30]. In addition, efforts are needed to secure this as an approved training period through a training program agreement. Training programs wish for elective time to be used in a rotation that is in line with health trainees’ future trajectories, in well-established training centres, and preferably in specific countries. It should be accounted for either by evaluations or logbooks of procedures and preferably spent in a place affiliated with an academic institute [29]. The only time that is completely under health trainees’ control and choice is their vacation time [29]. Therefore, it is not surprising that many health trainees will choose to sacrifice their time to participate in missions [29]. However, this time is limited, and studies have shown that the minimum suggested time for maximum benefit is approximately a month, excluding the predeparture preparation and return times [31]. Therefore, well-placed guidelines and pathways are of the utmost importance. Internationally, there are no unified funding sources for these missions, and they usually rely on multiple sources; however, most electives and aid trips are financed by the health trainees themselves. This is despite existing efforts to provide travel grants [32]. In our study, seven health trainees with experience in volunteerism relied on self-financing when they went abroad. Consistent with previous literature, our data showed that lack of funding remained a major concern for health trainees seeking such an experience [29,33]. Health trainees’ safety, whether from a medical point of view (e.g., infections, including HIV risk) or general safety, such as that regarding vehicle motor accidents or terrorism, was perceived as the next important barrier that held our health trainees from volunteering during missions. Locally, no clear guidelines or protective measures are dedicated to trainee safety. Internationally, personal safety has also been reported as a major concern for volunteer health trainees [34]. Numerous factors place health trainees at risk, such as unfamiliarity with the surroundings and new environments with different equipment at work and outside settings, in addition to exposure to unfamiliar pathogens, which increase the risk of severe infections in them [10]. Thus, multiple organisations are taking active steps to mitigate fear and ensure better protection [35]. One example is what The Medical Schools Council Electives Committee in the UK came up with in the form of a consensus statement that demonstrated in detail how to tackle the recurring concern regarding the safety of health trainees in international health electives [36]. Measures such as, and not limited to, extensive predeparture briefing, risk assessment, keeping a regular open line of communication and a designated emergency plan, as well as extensive debriefing after the trips, are helpful in that perspective [36]. Compared with our training programs, such guidelines exist in most programs that provide a well-established global health elective rotation [14]. The Global Health Task Force of the American Board of Pediatrics developed a comprehensive guide that incorporates global health education into training programs, which can also act as a resource for health trainees willing to take some volunteerism [14]. Most trainees will go on missions representing themselves without proper preparation, which may make them susceptible to numerous hazards, and sacrificing their vacation time will not make the trip count as part of their training [21]. Recently, a health trainee could be part of an outgoing trip, mainly a surgical trip, and a part of the treating team. However, it does not count toward training and should be organised in his/her own time. Moreover, their role in the team would not usually be well-established, and it would be considered volunteerism but not a part of training. Efforts are being made to rationalise these participants, but there are still no clearly drafted guidelines [30]. Hence, there is still a need for bridging bodies in mission-receiving centres to collaborate with postgraduate departments and the SCFHS, which are responsible for supervising training programs to approve such missions as established parts of training programs. Various organisational challenges remain, even in well-established settings and programs. For example, a survey of residency programs in the United States showed variable levels of experience and difficulties and encouraged more collaboration and coordination between training programs [22]. Although only seven of our participants had experience with volunteer missions at the time of the study, we felt it was important to report their opinions and experiences and compare them with the perceptions of the remaining participants in terms of expectations and potential barriers. Conversely, this limited number with experience reflects the importance of providing a structured and well-supported opportunity to health trainees willing to participate in volunteer missions to satisfy the high degree of enthusiasm reflected in our data. CONCLUSIONCoordinating health trainees’ missions through a unified authoritative body would provide better opportunities, override challenges and improve their perceptions and participation in these missions. It will also ensure a mutual benefit between the host and the sending country. The presence of a staff participating in these trips in the trainee’s environment had a positive impact. In this paper, we highlighted the most important challenges, and barriers from health trainees’ perspectives, which allowed us to come up with some recommendations for further improvement. Well-structured international health electives and voluntary medical trips with official global health rotations are an important part of a successful training program. Starting small with well-organised and coordinated short-term medical trips, and building up the opportunities as we get more experienced toward well-established global health programs and policies is worth the effort. Joining efforts between the SCFHSs, the coordinating body for health trainees, and the King Salman Center for Humanitarian Aid and Relief, the coordinating body for international outreach trips will help kick-start these trips. It will also help greatly with safety and ethical measures, predeparture preparation and postdeparture briefing. A continuous evaluation process utilising strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats will ensure successful continuity. ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors would like to thank all health trainees who participated in this study. CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. FUNDINGNone. ETHICAL APPROVALThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), study number RC16/139/R, with IRB reference number IRBC/860/16. The participants were informed through a request email about their rules, research cause and value, and their consent was considered implicit upon completing the survey. REFERENCES

Appendix A. Study instrument adapted with permission [16]. *Minor modification to current specialty.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Alkaabi NM, Aldubayee M, Masuadi E, Alwan IA, Babiker A. Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 Web Style Alkaabi NM, Aldubayee M, Masuadi E, Alwan IA, Babiker A. Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=172305 [Access: July 27, 2024]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Alkaabi NM, Aldubayee M, Masuadi E, Alwan IA, Babiker A. Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(2): 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Alkaabi NM, Aldubayee M, Masuadi E, Alwan IA, Babiker A. Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited July 27, 2024]; 23(2): 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 Harvard Style Alkaabi, N. M., Aldubayee, . M., Masuadi, . E., Alwan, . I. A. & Babiker, . A. (2023) Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudan J Paed, 23 (2), 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 Turabian Style Alkaabi, Nouf M, Mohammed Aldubayee, Emad Masuadi, Ibrahim Al Alwan, and Amir Babiker. 2023. Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (2), 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 Chicago Style Alkaabi, Nouf M, Mohammed Aldubayee, Emad Masuadi, Ibrahim Al Alwan, and Amir Babiker. "Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Alkaabi, Nouf M, Mohammed Aldubayee, Emad Masuadi, Ibrahim Al Alwan, and Amir Babiker. "Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.2 (2023), 187-198. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Alkaabi, N. M., Aldubayee, . M., Masuadi, . E., Alwan, . I. A. & Babiker, . A. (2023) Opportunities, barriers, and expectations towards international voluntary medical missions among health trainees in Saudi Arabia. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (2), 187-198. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1696628750 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Hafsa Raheel, Shabana Tharkar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 28-38

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.5

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12

Cited : 8 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mustafa Abdalla M Salih; Satti Abdelrahim Satti

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(2): 4-5

» Abstract

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Hasan Awadalla Hashim, Eltigani Mohamed Ahmed Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 35-41

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.4

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mutasim I. Khalil, Mustafa A. Salih, Ali A. Mustafa

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 10-12

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.1061585398078

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]