| Case Report Online Published: 22 Jun 2023 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 91-97 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 1 CASE REPORT Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literatureSandeep Jhajra (1), Akshada Sharma (2), Kumar Diwakar (1), Bhupendra Kumar Gupta (1), Sanjay Kumar Tanti (1)(1) Department of Paediatrics, Tata Main Hospital, Jamshedpur, India (2) Department of Paediatrics, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, India Correspondence to: Bhupendra Kumar Gupta Department of Paediatrics, Tata Main Hospital, Jamshedpur, India. E mail: bhupendra.gupta [at] tatasteel.com Received: 14 November 2021 | Accepted: 09 April 2022 How to cite this article: Jhajra S, Sharma A, Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Tanti SK. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(1): 91–97. https://doi.org/10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

ABSTRACTCoronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can adversely affect extra-pulmonary organs, such as the liver, heart and gastrointestinal tract apart from lungs. Although studies are showing that serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase are mildly elevated along with serum bilirubin in adult patients with mild to severe cases of COVID-19 disease, data are limited regarding liver injury in children infected with COVID virus. We report the case of a 9-year-old female patient who developed signs and symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection due to COVID-19 virus infection and subsequently developed fatty liver disease on follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the second case report in children showing an association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Keywords:Coronavirus; Liver injury; Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. INTRODUCTIONAs of the 1st of November 2021 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has affected more than 240 million people worldwide with more than 5 million deaths all over the world [1]. The first case of paediatric COVID-19 infection dates back to January 2020 wherein 10-year-old boy was infected in a family cluster of seven patients in China [2]. Most children infected with the coronavirus remain asymptomatic or have milder symptoms in the form of fever, cough, cold, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and fatigue [3–6]. However, few children have hyperinflammatory responses 4–6 weeks after COVID infection also known as multi-system inflammatory syndrome [7,8]. Current evidence suggests that apart from lungs, the virus may also adversely affect extra-pulmonary organs, such as the liver, heart and gastrointestinal tract [9]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus can cause liver damage directly by binding of coronavirus to angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor in bile duct epithelial cells after translocation of virus from gut to liver or indirectly by other mechanisms like a systemic hyperinflammatory response, liver hypoxia and ischaemia [10–12]. Although studies are showing that serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) are mildly elevated along with serum bilirubin in adult patients with mild to severe cases of COVID-19 disease [13], data is limited regarding liver injury in children infected with COVID virus, and the exact mechanism linking COVID-19 to paediatric fatty liver remains poorly understood due to its relatively asymptomatic course in paediatrics age group [12,14]. CASE REPORTWe report a case of a 9-year-old female with normal body mass index (BMI, weight was 33 kg with BMI of 19.5 kg/m2), who presented in our outpatient clinic with complaints of fatigue, loss of appetite and abdominal pain for 3–4 weeks. The patient had a history of an episode of upper respiratory tract infection in the form of fever, cough, cold and throat pain 6 weeks before present consultation, for which relevant investigations were taken. A nasopharyngeal swab for coronavirus real time-polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 was positive. The patient had been advised of home isolation and symptomatic treatment with paracetamol. On further investigations, liver transaminases, SGOT and SGPT were raised, 344.2 and 401.7 U/l, respectively. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 2.13 mg/dl (normal range=0.08–1.12 mg/dl). Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen was normal. Laboratory parameters of the index case are shown in Table 1. The patient became afebrile after 72 hours and tested negative for COVID-19 after 2 weeks. Table 1. Laboratory parameters of the index case.

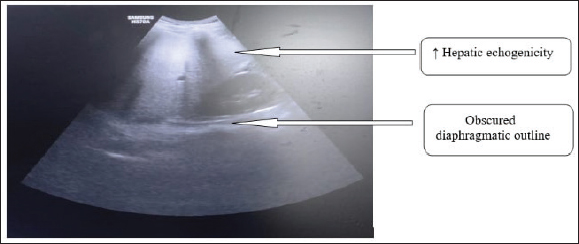

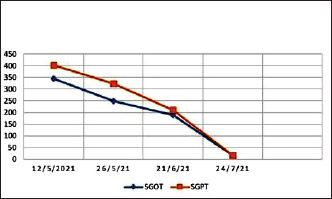

ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; Hb, Haemoglobin; APTT, Activated partial thromboplastin time; Hb, Haemoglobin; PT, Prothrombin time; SGOT, Serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; TLC, Total leukocyte count. The patient presented in our outpatient clinic after 6 weeks of initial COVID illness with complaints of persistent fatigue, loss of appetite and abdominal pain. On clinical examination, she was conscious, alert and having normal blood pressure with a saturation of more than 95% in room air. Vitals including body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate were normal with respect to age-matched controls. On auscultation chest was clear. The conjunctivae were clear without any redness or mucopurulent discharge. She did not have rash or petechiae over the body. The sclera was icteric. The cardiovascular examination was normal. There were no signs suggestive of clubbing, cyanosis or oedema. On abdominal examination, there was a dullness in the right hypochondrium region with non-tender hepatomegaly of 3 cm below the right costal margin with a smooth surface. Chest X-ray was unremarkable and 2D-echo suggestive of normal ejection fraction with no evidence of valvulitis. Laboratory evaluation revealed decreasing levels of liver transaminases with SGOT of 190.4 U/l and SGPT of 210.6 U/l, respectively. Other markers of liver damage in the form of serum albumin, serum bilirubin, prothrombin time (PT) and aPTT were within normal limits (Table 1). Serum albumin was 3.8 (normal=3.5–5.6 g/dl) along with a random blood sugar of 83 mg/dl. Renal function tests and serum electrolytes came normal. Further investigations performed for raised liver enzymes in the form of viral markers for hepatotropic viruses (hepatitis A, B, C and E), for leptospirosis and dengue were reported as normal. Workup for tuberculosis and typhoid was negative. Relevant investigations for cytokine storm, showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 8 mm at the end of first hour and CRP of 0.9 mg/dl (normal=0.08–1.12 mg/dl) with serum ferritin, interleukin-6 and D Dimer values of 50 (normal=25–300 ng/ml), 5.4 pg/ml (normal=0.5–6.4 pg/ml) and 510 (normal=0–500 ng/ml), respectively. Serum lactate dehydrogenase level was 300 (normal=150–500 mg/dl). SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody titre was <3.80 AU/ml (negative, reference value <12.0 AU/ml). USG of the abdomen was suggestive of increased liver span and increased hepatic echogenicity with the blurring of portal/hepatic vein suggestive of fatty liver disease (Figure 1). A thorough evaluation is needed to differentiate infective, metabolic and autoimmune causes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in children, but due to gradual decline in liver enzymes and significant clinical improvement over the time workup for autoimmune causes, 24-hour urine copper or liver biopsy were not considered. Supportive therapy in the form of multivitamins and dietary advice was given. She was kept on follow-up. Liver enzymes came down to normal after 12 weeks with a reduction in liver size (Figure 2).

Figure 1. USG of abdomen showing increased liver span and increased hepatic echogenicity (arrow) with the blurring of portal/hepatic vein and obscured diaphragmatic outline (arrow).

Figure 2. Fall of liver transaminases over time in the index case. *SGOT, Serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase. DISCUSSIONChildren with COVID-19 infection have less severe symptoms and most of them present with milder manifestation in form of upper respiratory tract infection. In contrast to COVID-19 infection in adults, incidence of severe and fatal COVID-19 infection is less frequent in children. It is yet not well understood whether this age-related difference in severity is related to differential expression of ACE-2 receptor or lesser prevalence of co-morbidities or due to differential immune response to virus [13,15–17]. It has been postulated that cross-reactive antibodies due to repeated upper respiratory tract infections may confer protection against microbes with similar antigenic epitopes [17–19]. Furthermore, it has been postulated that Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination may build up CD + 4 T helper 1 immunity, providing some protection against COVID-19 due to the cross-over immunity [20,21]. COVID-19-related liver injury is extrapulmonary manifestation of the disease and is characterised by variable degrees of liver damage due to the disease or its treatment in a patient with or without pre-existing liver disease [22]. Paediatric NAFLD is defined as hepatic steatosis in children aged ≤18 years in the absence of genetic diseases, metabolic disorders, infections like hepatitis C, use of steatogenic drugs, alcohol consumption or malnutrition [23]. Deranged liver enzymes are often observed in patients with COVID-19 usually in the form of elevated hepatic transaminases (SGPT and SGOT). Less frequently, mild elevations in gamma-glutamyl transferase, ALP and total bilirubin have also been reported. However, a significant impairment of liver function resulting in death in COVID-19 may occur rarely [24–27]. The aetiology of liver impairment is likely to be multifactorial, and includes direct liver damage by virus-induced cytopathic effect, immune-mediated inflammatory response, hypoxic injury associated with pneumonia and sepsis and liver injury caused by the use of hepatotoxic drugs [28,29]. In the index case liver enzymes were raised before the administration of paracetamol and therefore, we can completely exclude the possibility that any SGOT/SGPT abnormality caused by drug-induced injury. Duan et al. [30] showed elevated serum levels of IL-1beta, IL-6, and IL-10 in COVID-19 patients with increased SGPT as compared to those patients with normal SGPT. However, Zhou et al. [31] showed no difference in levels of serum interleukins (IL-6 and IL-10) between COVID-19-infected children with and without elevated serum liver enzymes, indicating that interleukins may have questionable role in the pathogenesis of liver injury in COVID-19 paediatric patients]. Our index case has slightly elevated CRP (2.13 mg/dl), however, serum ferritin and serum interleukins were within normal limit. COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory conditions (MIS-C) which can present with liver and gastrointestinal involvement was ruled out in our case as our patient doesn’t meet the case definition of MIS-C given by World Health Organization [7,32,33]. Of interest, Cai et al. [34] study reported elevated transaminases at admission in COVID-19 children and adult patients due to the direct cytopathic effect of coronavirus infection on hepatocytes. A study from Italy shows an association between hepatic steatosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection in children [35]. In our case, the patient didn’t have underlying liver disease and liver impairment was found at first presentation of COVID-19 infection suggesting the possibility of direct cytopathic effect of coronavirus. Due to the gradual decline in liver enzymes, significant clinical improvement over time and financial constraints workup for autoimmune causes, 24-hour urine copper or liver biopsy were not considered. Our patient presented with hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver with mild respiratory symptoms adding to the spectrum of the illness that SARS-CoV-2 can present in children. The patient had a mild illness, did not have hypoxemia, pneumonia or cardiac dysfunction. Apart from SARS-CoV-2 infection, no other infectious aetiologies to explain persistent hepatitis and NAFLD were found. CONCLUSIONThis case report shows the spectrum of the presentation of COVID-19 infection in children and a unique association of coronavirus disease and fatty liver with hepatitis in children. Hepatic impairment can be observed in mild infection and patients with hepatitis should be investigated for COVID-19 infection during the pandemic time along with workup for other hepatotropic infections. NAFLD in COVID-19-exposed children warrant prolonged follow up. Further studies are required to determine the incidence and severity of hepatic involvement and to understand the underlying mechanism. CONFLICT OF INTERESTSThe authors declare no conflict of interests. FUNDINGNone. ETHICAL APPROVALSigned informed consent for participation and publication of medical details was obtained from the parents of this child. Confidentiality of patient’s data was ensured at all stages. The authors declare that ethics committee approval was not required for this case report. REFERENCES

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Jhajra S, Sharma A, Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Tanti SK. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 Web Style Jhajra S, Sharma A, Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Tanti SK. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=2755 [Access: February 05, 2026]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Jhajra S, Sharma A, Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Tanti SK. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Jhajra S, Sharma A, Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Tanti SK. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited February 05, 2026]; 23(1): 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 Harvard Style Jhajra, S., Sharma, . A., Diwakar, . K., Gupta, . B. K. & Tanti, . S. K. (2023) Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudan J Paed, 23 (1), 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 Turabian Style Jhajra, Sandeep, Akshada Sharma, Kumar Diwakar, Bhupendra Kumar Gupta, and Sanjay Kumar Tanti. 2023. Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 Chicago Style Jhajra, Sandeep, Akshada Sharma, Kumar Diwakar, Bhupendra Kumar Gupta, and Sanjay Kumar Tanti. "Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Jhajra, Sandeep, Akshada Sharma, Kumar Diwakar, Bhupendra Kumar Gupta, and Sanjay Kumar Tanti. "Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.1 (2023), 91-97. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Jhajra, S., Sharma, . A., Diwakar, . K., Gupta, . B. K. & Tanti, . S. K. (2023) Acute hepatitis with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-expanding clinical spectrum in COVID-19 exposed children: case report and review of literature. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 91-97. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1636877693 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12