| Case Report Online Published: 05 Jul 2023 | ||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 104-107 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 1 CASE REPORT Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiographyPushpinder S. Khera (1), Pawan K. Garg (1), Gautam R. Choudhary (2), Tushar Suvra Ghosh (1), Sarbesh Tiwari (1), Bharat Choudhary (3)(1) Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Jodhpur, Jodhpur, India (2) Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Jodhpur, Jodhpur, India (3) Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Jodhpur, Jodhpur, India Correspondence to: Pawan Kumar Garg Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Jodhpur, Jodhpur, India. Email: drgargpawan [at] gmail.com Received: 05 October 2020 | Accepted: 18 February 2023 How to cite this article: Khera PS, Garg PK, Choudhary GR, Ghosh TS, Tiwari S, Choudhary B. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(1):104–107. http://doi. org/10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

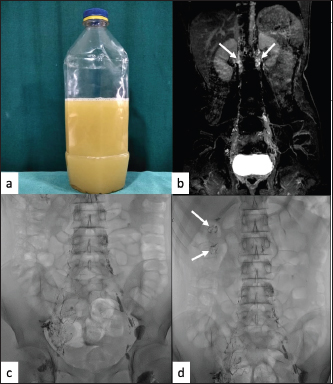

ABSTRACTChyluria is a rare entity characterised by the presence of chyle/lymphatic fluid within the urine. It develops following an abnormal communication between the perirenal lymphatics and pelvicalyceal lymphatics. There are multiple causes of chyluria including infective (filariasis), post-traumatic, post-surgical, pregnancy and malignancy. We present a case of a 15-year-old male who presented with a complaint of the intermittent passage of milky urine for the preceding 1 year. Conventional lipiodol lymphangiography followed by cone beam computed tomography was done to look for abnormal fistulous channels. Subsequently, the patient was successfully treated with cystoscopy-guided renal pelvic instillation sclerotherapy of povidone-iodine. KEYWORDS:Chyluria; Conventional lipiodol lymphangiography; Lympho-pelvicalyceal fistula. INTRODUCTIONChyluria, though a benign condition, is debilitating and may cause significant weight loss, cachexia, malnutrition, hypoproteinaemia and immunosuppression [1]. The most common cause of chyluria is filariasis infection in endemic areas such as India, Japan, North Africa, South-east Asia and South America. We here describe a case of non-filarial chyluria which is relatively uncommon. Right-sided lymph-pelvicalyceal fistula was demonstrated by using conventional lipiodol lymphangiography (CLL) and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) which helped in the management of chyluria by single-sided renal pelvic instillation sclerotherapy (RPIS). CASE REPORTA 15-year-old male presented with a complaint of the intermittent passage of milky urine (Figure 1a) of 1-year duration associated with weight loss of 8 to 9 kg. There was no history of fever or abdominal pain. No history of trauma, surgery, hospitalisation, contact history with a tuberculosis patient or urinary infection was present. General physical examination was normal with no facial or limb edema noted. Urine biochemical examination revealed the presence of triglycerides and chylomicrons, which suggested chyle in urine. All other investigations including urine for protein, microfilarial antigen test, malarial antigen test, etc were within normal limits. Dynamic contrast magnetic resonance lymphangiography (DCMRL) showed opacification of pelvic as well as bilateral retroperitoneal lymphatic channels (Figure 1b), but no definite communication with pelvicalyceal lymphatics was identified. For further evaluation, CLL was performed by direct intranodal injection of total of 10 ml of lipiodol (iodinated ethyl ester of fatty acids of poppy seed oil) into bilateral inguinal lymph nodes under digital subtraction angiography (DSA) machine. On the right side, multiple distorted lymphatic channels were opacified in groin and pelvis without opacification of interval lymph nodal stations (Figure 1c). After 40–45 minutes of intermittent fluoroscopy, a few abnormal lymphatics were seen in the right renal region (Figure 1d).

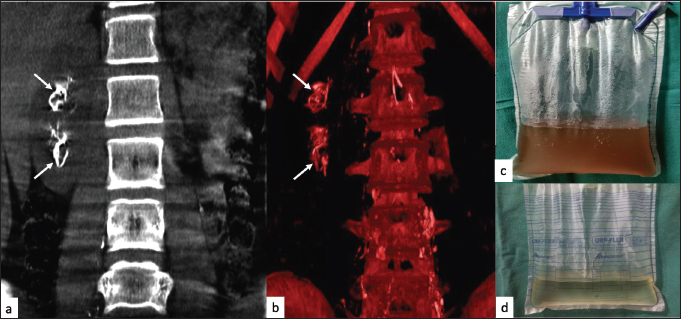

Figure 1. (a) Sample of patient’s urine showing gross chyluria. (b) DCMRL coronal image showing bilateral paravertebral lymphatic channels (arrows). (c) CLL image showing multiple ill-defined channels in the right inguinal and hemi pelvis. Normal lymphatic channels and lymph nodes are seen on the left side. (d) CLL image showing lipiodol pooling in the right renal area taking the shape of calyces (arrows). Subsequent CBCT was performed on the DSA table which involved a 240-degree rotation of an X-ray tube around the patient and the acquisition of computed tomography-like images in orthogonal planes. It demonstrated multiple abnormal lymphatics around the right pelvicalyceal system with lipiodol contrast within the right pelvicalyceal system, which strongly suggested a right-sided lympho-pelvicalyceal fistula (Figure 2a and b). The patient was followed conservatively for a week to look for the therapeutic effect of lipiodol, but no improvement in chyluria was seen. He underwent a cystoscopy which confirmed milky urine from the right ureteric orifice only, with the placement of the right ureteric catheter. RPIS was performed only on the right side using 0.2% povidone-iodine (total daily dose of 5–6 ml) for three consecutive days three times a day. Post-completion of 3rd instillation of povidone-iodine, he had a clearance of urine turbidity (Figure 2c) and complete clearance on day three (Figure 2d). He didn’t complain of any flank pain, nausea, vomiting or fever post-RPIS. Repeat renal function test and ultrasound at one month was normal with no evidence of hydronephrosis or calyectasis. The patient was followed for six months with no recurrence. DISCUSSIONThe most common cause of chyluria is a parasitic infection due to Wucheraria bancrofti in endemic areas. Other nonparasitic causes of chyluria include tuberculosis, congenital anomalies, trauma, post-surgery infections and malignancy [2]. Rarely genetic association between Mannose-binding lectin 2 gene polymorphisms at codon 221 promoter region is linked with filarial chyluria [3]. In children, chyluria is often confused with the nephrotic syndrome. Differentiating between the two is necessary. For example, haematuria due to the rupture of blood vessels near the abnormal fistulous connections and renal colic due to clots can occur in chyluria but is not seen in classical nephrotic syndrome [4].

Figure 2. CBCT in coronal (a) plane and volume rendering (b) confirming lipiodol within the right renal pelvicalyceal system (white arrows). (c) Clearance of urine turbidity after the third installation of RPIS. (d) Complete clearance of urine on the third day of RPIS. Mechanism of development includes obstruction in the retroperitoneal nodes and lymphatics between the intestinal and thoracic ducts. This leads to stasis, retrograde flow of lymph into the renal pedicle lymphatics, causing their dilatation, proliferation and subsequent rupture into the pelvicalyceal system resulting in renal lympho-pelvicalyceal fistula [5]. Chyluria can be classified into three grades, mild, moderate and severe based on the severity of chyle passage into urine, weight loss, and involvement of calyx on retrograde pyelography [6,7]. In our case, severe chyluria was present with the continuous passage of milky urine associated with weight loss. Investigation to diagnose and locate the origin of chyluria includes; non-contrast Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), DCMRL, CLL, lymphoscintigraphy and retrograde pyelography. Cystoscopy is used for diagnosis as well as treatment [8]. MRI may include a heavily T2-weighted sequence or DCMRL. It may detect an abnormality, however, sensitivity is low in most of the cases. CLL, which requires direct injection of lipiodol into inguinal lymph nodes, is most sensitive in the detection of abnormality due to superior spatial resolution. If we combine CBCT in the same sitting, we can get cross-sectional images which further increase the sensitivity of detection of chyle leak. In case of intermittent chyluria, cystoscopy without prior imaging may lead to a false negative result or unnecessary bilateral treatment even when pathology is unilateral. Treatment of chyluria includes conservative, CLL with or without lymphatic embolization, minimal invasive treatment like RPIS or surgery. Conservative measures include bed rest, high fluid intake, a low-fat diet, and fat-containing medium-chain triglycerides. Anti-filarial agents are useful in diagnosed cases of filariasis. The other advantage of CLL is its therapeutic role in stopping chyle leakage. Matsumoto et al. [9] described the effectiveness of lymphangiography in stopping chyle leaks in eight out of nine cases including chylothorax, chylous ascites and lymphatic fistula. The mechanism proposed for the therapeutic effect of CLL includes activation of inflammatory reaction by leakage of lipiodol in the soft tissue; the blockage of distal lymphatics by lipiodol acting as an embolic agent, and compression by the mass of leaked lipiodol on the leaking lymphatics [9]. Hence CLL is useful if conservative treatment fails and before planning for surgical or other treatment. Percutaneously accessing the lymphatic tissue/lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum close to the renal hilum and injecting n-Butyl cyanoacrylate glue is one minimally invasive method to treat chyluria [8]. Many sclerosing agents described for RPIS but commonly used are silver nitrate and povidone-iodine. This sclerosant induces an inflammatory reaction in the lymphatics leading to initial chemical lymphangitis, later fibrosis and blockage of lymphatics, leading to closure of lymphatic pelvic communication [2,10,11]. Although RPIS is relatively safe, it can lead to hydronephrosis, calyectasis or renal scarring. Surgical techniques include open surgery or retroperitoneoscopic renal pedicle ligation of lymphatic disconnection [12]. In our case, CLL confirmed the diagnosis of lympho-pelvicalyceal fistula and also lateralised the pathology, so that unilateral RPIS was done effectively. Despite its mild invasiveness, CLL is a good investigation for the diagnosis of chyluria and has a therapeutic role in some cases by closing the fistula. Combining CBCT with CLL further increases the chances of detection of pathology. CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. FUNDINGNone. ETHICAL APPROVALSigned informed consent for participation and publication of medical details was obtained from the parents of the patient. Confidentiality was ensured at all stages. The authors declare that ethics committee approval was not required for this case report. REFERENCES

| ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Khera PS, Garg PK, Choudhary GR, Ghosh TS, Tiwari S, Choudhary B. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 Web Style Khera PS, Garg PK, Choudhary GR, Ghosh TS, Tiwari S, Choudhary B. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=5721 [Access: February 05, 2026]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Khera PS, Garg PK, Choudhary GR, Ghosh TS, Tiwari S, Choudhary B. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Khera PS, Garg PK, Choudhary GR, Ghosh TS, Tiwari S, Choudhary B. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited February 05, 2026]; 23(1): 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 Harvard Style Khera, P. S., Garg, . P. K., Choudhary, . G. R., Ghosh, . T. S., Tiwari, . S. & Choudhary, . B. (2023) Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudan J Paed, 23 (1), 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 Turabian Style Khera, Pushpinder S., Pawan K. Garg, Gautam R. Choudhary, Tushar Suvra Ghosh, Sarbesh Tiwari, and Bharat Choudhary. 2023. Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 Chicago Style Khera, Pushpinder S., Pawan K. Garg, Gautam R. Choudhary, Tushar Suvra Ghosh, Sarbesh Tiwari, and Bharat Choudhary. "Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Khera, Pushpinder S., Pawan K. Garg, Gautam R. Choudhary, Tushar Suvra Ghosh, Sarbesh Tiwari, and Bharat Choudhary. "Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.1 (2023), 104-107. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Khera, P. S., Garg, . P. K., Choudhary, . G. R., Ghosh, . T. S., Tiwari, . S. & Choudhary, . B. (2023) Chyluria: clearing the ‘muddiness’ with lipiodol lymphangiography. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 104-107. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1601720841 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12