| Original Article Online Published: 27 Jun 2023 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 21-31 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unitUsha Devi (1), Prakash Amboiram (1), Ashok Chandrasekaran (1), Umamaheswari Balakrishnan (1)(1) Department of Neonatology, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, India Correspondence to: Umamaheswari Balakrishnan Department of Neonatology, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, India. Email: drumarajakumar [at] gmail.com Received: 24 January 2022 | Accepted: 18 November 2022 How to cite this article: Devi U, Amboiram P, Chandrasekaran A, Balakrishnan U. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(1):21–31. https://doi.org/10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

ABSTRACTNeonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission increases parents’ stress levels and it might be even higher in the crisis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown. This study was done to identify the stress levels of parents of admitted neonates and the difficulties encountered in neonatal care and follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. The Parental Stressor Scale (PSS:NICU) and Perceived Stress Scale (PeSS) were used to identify the stress levels of parents of admitted neonates. Online survey form with a structured questionnaire comprising PeSS and NICU:PSS was sent through messaging app (Google form) after informed consent. PSS score of <14 was considered low stress, 14–26 moderate and >26 as high. A total of 118 parental responses (mother /father in 26, both in 46) for 72 admitted neonates, were obtained. The mean (SD) PeSS score was 19.7 (5.8%) and 92 (78%) had moderate stress while 11 (9%) had high stress. In NICU:PSS, sights-sounds and parental role had more median scores: 2.25 (1–3.75) and 2.21 (1–3.57), respectively. Maternal and paternal NICU:PSS (p-0.67) and PeSS (p-0.056) scores were not statistically different. Keeping nil per oral, invasive ventilation, culture-positive sepsis, fathers’ transport difficulty and longer duration of mothers’ and neonates’ hospital stay was associated with increased NICU: PSS scores. Twenty (29%) parents could not bring their child for follow-up and there was a delay in immunisation in 21 (30%). The pandemic and the lockdown might have disrupted antenatal and postnatal follow-ups further adding to the parental stress. Keywords:COVID-19; Neonatal intensive care unit; Parents; Stress; Follow-up. INTRODUCTIONThe outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has created a global health crisis. Apart from the virus and its pattern of transmission, the safety measures to curtail its spread like the restriction of people movement and lockdown also has affected the health care system. The pandemic and the response to the pandemic affected both the provision and utilisation of maternal, newborn and child health services. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic increases mortality directly as well as indirectly [1]. Telephonic communication for counselling during the hospital stay as well as post-discharge was encouraged by various organisations [2]. The parent-neonate bonding process gets disrupted when the infant spends the first several days or weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Neonatal admission and the NICU environment are major factors contributing to the parents’ distress. To date, there are very few studies quantifying stress levels among parents of babies admitted in NICU from developing countries [3,4]. Though most of such studies and similar ones from Western countries are more representative of mothers’ stress [4–6], the stress in the fathers’ using Parental Stressor Scale (PSS): NICU has also been assessed by a few [6–8]. Before the pandemic, both mother and father were allowed throughout the day to see and stay near their baby in our NICU. After the COVID-19 pandemic, there were a lot of policy changes in the hospital: fathers’ entry was restricted to 2 hours in the morning; in case the mother tested positive for COVID, asymptomatic babies were nursed along with their mothers in isolation rooms in COVID wards with all contact precautions. Currently, in this crisis of COVID-19 pandemic, the parental stress during the hospital stay and difficulties encountered in the antenatal and postnatal period will be even higher. Rapid changes in hospital and NICU entry policies related to COVID-19 affecting the parental presence for NICU admitted neonates, the fear of acquiring infection to self and their baby, decreased follow-up services, and also the limitations in support staff have a substantial impact on parental and family well-being [9,10]. Evaluating the stress levels in the parents during the pandemic will help us in improving NICU and hospital environment to address and reduce the same in the future. We conducted this study to understand the stress levels in parents of neonates admitted to our NICU, difficulties during the antenatal and postnatal period, and to find out the maternal, neonatal and logistic factors significantly increasing their stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. MATERIALS AND METHODSThis was an observational study done in the level III NICU, Chennai, India, after Institutional ethics committee approval (IEC-NI/20/75/43). The study was registered with CTRI (CTRI/2020/05/025428). We included parents of the babies admitted to NICU between March 2020 and July 2020 during the lockdown period. The eligible parents who can read and respond to English questionnaires were approached over the phone or during follow-up in the newborn clinic. The link for the structured English questionnaire was sent through messaging app (WhatsApp, thus following social distancing norms) for those who consent to participate in the study. Consent was obtained by a link in the online survey form (Google form) before proceeding to the further questions (https://forms.gle/bXEhuK3hvetwuuYv5). Both father and mother filled the form independently. Baseline maternal and neonatal characteristics were also collected and entered in a structured proforma. QuestionnaireA set of questions related to antenatal and perinatal care were framed after feedback from 10 parents who consented and filled the form, individual and focused group discussion and expert opinion obtained through online meetings from 10 neonatologists in the city. Accordingly, the questionnaire was modified/simplified before starting the study. It encompassed questions related to antenatal care, postnatal care, difficulties encountered during the antenatal period and postnatal NICU stay due to the pandemic and stress related to it, difficulties in post-discharge follow-up and feeding, scoring on perceived and parents stress scale. Scores ranging from ‘not applicable’ (0) and ‘not at all stressful’ (1) to ‘extremely stressful’ (5) were given on a Likert-type scale.

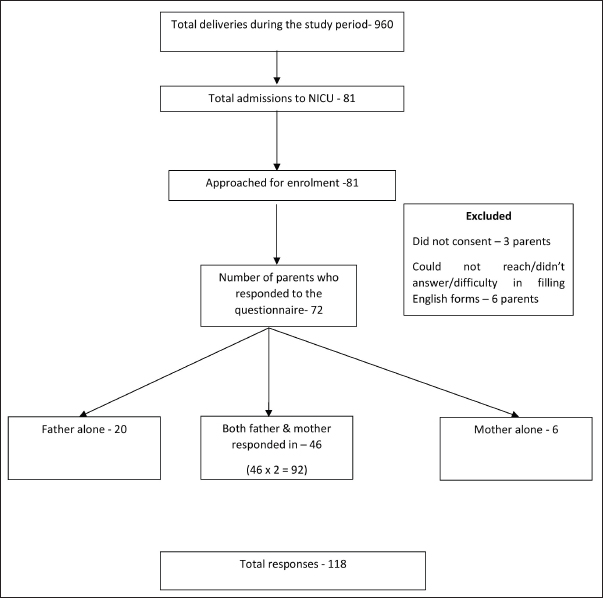

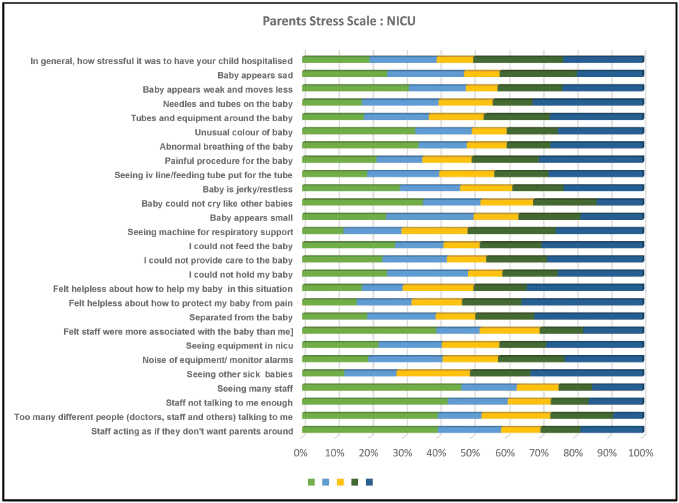

Figure 1. Study flow diagram. Stress scoresValidated stress scores: PSS:NICU and 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PeSS) were also incorporated into the questionnaire. PSS:NICU has a total of 27 parameters and 4 subscales: infant looks and behaviour (ILB), parental role alteration (PRA), sights and sounds (SS) and staff behaviour (SB). We also used PeSS-10, the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring stress. The items are easy to understand, and the response alternatives are simple to grasp. Because levels of appraised stress are usually influenced by major events and changes in coping resources, the predictive validity of the PeSS is expected to be high for 4–8 weeks [11]. This score has been used to find out the perceived stress of quarantine, isolation during the COVID pandemic [12,13]as well as following natural disasters [14]. Higher perceived stress has also been found to be associated with depression [15]. The 10-item PeSS has 10 questions and a score of 0 stands for never and 4 for often. Perceived stress scores were obtained by reversing responses (0=4, 1=3, 2=2, 3=1, 4=0) to the four positively stated items (items 4, 5, 7 and 8) and then summing across all scale items. A score of 0–13 was considered low stress, 14–26 as moderate stress and 27–40 as high perceived stress. OutcomesThe primary outcome was the stress level of parents of admitted neonates as assessed using the parent stress scale (PSS:NICU) and the PeSS. Secondary outcomes included the impact of maternal and neonatal characteristics on parents’ stress scores, the difference in the mothers’ and fathers’ stress levels, the nature of feeding in neonates, COVID precautions and difficulties encountered in neonatal care and follow-up. Statistical analysisStress scores of father and mother were compared using an independent two-sample t-test, and Extended Mc-Nemar test. Maternal, neonatal and logistic factors contributing to high-stress scores were identified by the Mann-Whitney U test for two groups and Kruskal Wallis test for ≥3 groups. SPSS version 21.0 was used for analysis. RESULTSOut of the 81 admissions to NICU, parents of 72 babies responded to the questionnaire with both the parents responding in 46, father alone in 20 babies and mother in 6 (Figure 1). Prematurity was the most common reason for admission (44%) followed by babies admitted for transient tachypnoea of the newborn (18%), intrauterine growth restriction, hypernatremic dehydration and babies born to COVID positive sick mothers (6% each), sepsis (4%), hypoglycaemia (4%), jaundice, post-resuscitation care and fever evaluation (3% each), low birth weight care, hypoglycaemia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, congenital heart disease, hypotonia and persistent vomiting (1% each). Twenty-two babies and 50 babies were delivered by vaginal delivery and caesarean section, respectively. Obstetrics complications observed were pregnancy-induced hypertension (nine mothers), gestational diabetes mellitus in eight, and gestational thrombocytopenia in one. Four mothers had COVID infection. The mean (SD) PeSS score was 19.7 (5.8) with 92 (78%) respondents rating the stress as moderate and 11(9%) as high (Table 1). Under PSS:NICU, 21% of the respondents rated hospitalisation of the neonate as extremely stressful. For parameters under baby looks, behaviour, parental role and SS, 7%–26% felt extremely stressful. For parameters under staff behaviour, only 5%–9% felt extremely stressful (Figure 2). Median scores were higher for the subscales SS (2.25 [1–3.75]), PRA (2.21 [1–3.57]) than the ILB (1.75 [1.07–2.86]) and SB (1 [0–2.67]). Fathers’ and mothers’ total PSS:NICU (2.07 [1.12] vs. 2.13 [0.17], p-value 0.672) and PeSS scores (18.83 [6.77] vs. 20.33 [4.97], p-value 0.056) were not statistically different. Neonatal factors like culture-positive sepsis, invasive ventilation, not feeding with mother’s milk on day 1, hospital stay for >5 days were all associated with high PSS:NICU scores (Table 2). Not feeding with mother’s milk by day 1 and ROP requiring treatment were associated with high PeSS scores. Among the maternal factors, a longer duration of the mother’s hospital stay significantly increased the NICU:PSS scores. Difficulty in transportation for father/relatives to hospital increased both the NICU:PSS and PeSS scores (Table 3). One-fourth of the parents were not able to complete all scheduled antenatal scans and check-ups. Only 41 (59%) babies were on exclusive breastfeeding on follow-up, and 21 (30%) babies had a delay in newborn follow-up and immunisation (Table 4). DISCUSSIONVarious scores were used to assess stress in parents of neonates admitted to NICU like PSS:NICU, neonatal unit parental stress scores and patient-reported outcomes measurement information system [16–19]. We used PSS:NICU score in our study [16]. In the study by Polloni et al. [20], high levels of depression and anxiety were observed among NICU families with more than half of the parents scoring over the cut-off for anxiety and almost one-quarter over the cut-off for risk of depression. About one-third of parents reported extreme/high stress and a relevant negative impact on the experience of becoming parents specifically due to the pandemic. Around half of the respondents rated the stress of having their child hospitalised as much or extreme even in our study. Table 1. Impact of maternal and neonatal characteristics (parents of 72 babies) on the stress scores.

¶Mann Whitney U test. PSS:NICU, Parental stressor scale: neonatal intensive care unit; PSS, Perceived stress scale. Bold numbers are significant p values. p-value < 0.05 is considered significant. PRA was the greatest source of stress for both mothers and fathers in the meta-analysis by Caporali et al. [21]. Even in our study, median scores were higher for the subscales sights, sounds and PRA. During our study, the lockdown could have further limited the interaction between parents and the neonate in NICU thus increasing the stress score and in particular, stress due to PRA.

Figure 2. PSS:NICU for general NICU stay, baby looks and behaviour (12 parameters), parental role (7 parameters), sight and sounds (4 parameters) and staff behaviour (3 parameters). NICU, Neonatal intensive care unit. Table 2. Impact of maternal and neonatal characteristics (parents of 72 babies) on the stress scores.

¶Mann Whitney U test. PSS:NICU, Parental stressor scale: neonatal intensive care unit; PSS, Perceived stress scale. Bold numbers are significant p values. p-value < 0.05 is considered significant. Table 3. Impact of logistic issues on stress scores.

¶Mann Whitney U test; aKruskal Wallis test. PSS:NICU, Parental stressor scale: neonatal intensive care unit; PSS, Perceived stress scale. Bold numbers are significant p values. p-value < 0.05 is considered significant. Table 4. Impact of lockdown on antenatal and postnatal care.

In the study by Dudek-Shriber [22], on parental stress in NICU, stress scores of mothers were significantly higher compared to that of fathers. Though there was a trend of increased perceived stress scores in mothers, both the PSS:NICU and PeSS scores were not statistically different between fathers and mothers in our study. The pandemic and the associated logistic difficulties could have increased the stress levels in fathers as well. Factors such as parent gender, how soon they saw and held their infant after birth, perceived risk of infant mortality, low birth weight and low gestation age have been associated with increased parental stress in previous studies [23–26]. However, in the meta-analysis by Caporali et al. [21], infants’ neonatal characteristics (gestational age and birth weight) and clinical conditions (comorbidities) did not influence the stress scores. In our study, culture-positive sepsis, invasive ventilation, mother’s milk not given on day 1 and longer duration of hospital stay were associated with higher PSS:NICU scores. This might be indirectly due to the increased sickness level of the neonate, lesser opportunity to witness improvement in the status due to transport and visitation restrictions. In our study, ROP needing treatment increased the PeSS scores probably because parents responded to the questionnaire at discharge or follow up and ROP was the only ongoing event during this time and the baby was already out of the acute phase by that time. Around 20%–30% of the parents missed antenatal check-ups and postnatal follow-ups/immunisation. Roberton et al. [1] also in their study on indirect effects of COVID-19 in low-middle income countries have estimated a 45% reduction in essential services coverage. The fear of contracting an infection during hospital visits and transportation restrictions could have led to delayed or inadequate visits to the hospital during the antenatal and postnatal period. The exclusive breastfeeding rate at discharge from the unit decreased from more than 95%–80% probably due to less contact time between mother and infant due to the pandemic or increased stress levels in the mother. Few studies regarding doctor-patient communication suggest that, despite physical separation, teleconsultation is not inferior to communication during face-to-face visits and it depends on technical and behavioural aspects of system experience [27,28]. In the study by Kludacz-Alessandri et al. [29], 33.3% of patients did not agree that teleconsultation was as good as meeting their general practitioner face to face. Around 10% of the respondents in our study were also not confident even after phone consultation after discharge and felt offline consultation would have been more reassuring. Various factors postulated for decreased satisfaction rates during telecommunication are no possibility of direct examination, internet issues and lack of video consultation due to technical issues [29]. Strengths of our study are the good response rate (89%), addressing the stress related to logistic issues as well, usage of perceived stress score with good validity and the response being done at or after discharge of the baby from NICU, thus facilitating honest appraisal regarding the staff behaviour by the participants. Limitations of the study beingNon-availability of pre-COVID stress scores and stress levels during different periods of NICU stay. Hence, the stress cannot be fully attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Assessment and analysis of stress scores after the pandemic can help in implementing strategies to reduce the parental stress. CONCLUSIONMaternal factors, neonatal morbidity and logistic difficulties due to the pandemic might increase the parental stress. Family-centred care and frequent blended (online and offline) antenatal and postnatal consultation during pandemic might rejuvenate and keep us ready to bring down the parental stress in the future. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTThe authors would like to thank Margaret S. Miles (PhD, FAAN, Professor Emerita, UNC CH Nursing) for the permission to use PSS:NICU. CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare that they have no competing interests. FUNDINGNone. ETHICAL APPROVALThis study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Research in Human Subjects (IEC-NI/20/75/43; registered with CTRI: CTRI/2020/05/025428). Informed consent was obtained from parents of babies included in the study. REFERENCES

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Devi U, Amboiram P, Chandrasekaran A, Balakrishnan U. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 Web Style Devi U, Amboiram P, Chandrasekaran A, Balakrishnan U. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=14827 [Access: February 05, 2026]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Devi U, Amboiram P, Chandrasekaran A, Balakrishnan U. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Devi U, Amboiram P, Chandrasekaran A, Balakrishnan U. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited February 05, 2026]; 23(1): 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 Harvard Style Devi, U., Amboiram, . P., Chandrasekaran, . A. & Balakrishnan, . U. (2023) COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudan J Paed, 23 (1), 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 Turabian Style Devi, Usha, Prakash Amboiram, Ashok Chandrasekaran, and Umamaheswari Balakrishnan. 2023. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 Chicago Style Devi, Usha, Prakash Amboiram, Ashok Chandrasekaran, and Umamaheswari Balakrishnan. "COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Devi, Usha, Prakash Amboiram, Ashok Chandrasekaran, and Umamaheswari Balakrishnan. "COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.1 (2023), 21-31. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Devi, U., Amboiram, . P., Chandrasekaran, . A. & Balakrishnan, . U. (2023) COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: impact on parents’ stress level and infant care in a tertiary neonatal unit. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 21-31. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1643018753 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12